“There is your mind. In your mind is a door. Behind the door is the truth. Can you open that door?” These words set the tone for Jude Idada's award-winning psychological thriller, Kofa. After this fine poetic prologue, we are plunged into a world of claustrophobic disarray and technological humour.

Set against the backdrop of Lagos, the movie unfolds with a non-linear, time-reversed structure, merging two timelines into a complex narrative. It begins with a sense of disorientation that reflects the experience of its characters: eight individuals who wake up in a dark, confined space with no recollection of who they are beyond their names.

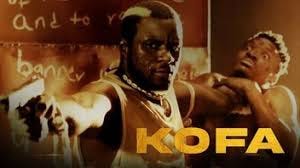

The protagonists, clad only in their underwear, struggle to remember their identities and the circumstances that led to their predicament. As they grapple with their confusion, trying to recollect their past, the threat of an armed assailant picking them off one by one heightens the stakes. This intriguing plot gives the movie an air of mystery and tension, compelling us to piece together the puzzle along with the characters.

The film’s claustrophobic setting intensifies the psychological tension among the characters. The small, closed room marked with various inscriptions becomes a pressure cooker where fear, suspicion, and paranoia simmer. Idada creatively uses this confined space to explore the characters' psyches, creating an atmosphere of impending doom. The sparse set design and tight framing reinforce the feeling of entrapment and the darkness of the human mind, making us share in the characters' anxiety.

Parallel to the characters’ plight, an intelligent company deploys drones across the city in a search mission. The subplot introduces a male voice in the surveillance room. His commentary provides a stark contrast to the dire situation of the captives. His remarks on economic disparities in Lagos, Nigerian superstitious beliefs in witchcraft, and football banter add a touch of dark, almost absurdist humour to the film. Beyond the comic relief, his commentaries indicate the casual detachment of those in the government from the citizens’ suffering. It’s an incisive subtext running parallel to the captives' ordeal.

Kofa’s first and second acts are confusing, and the acting is capricious. The characters’ efforts to piece together their identities and escape their captor are marked by witty dialogue and introspective vulnerability. However, the film’s attempts at being overly clever occasionally risk alienating us. The non-linear narrative and intricate plot twists demand close attention. At times, the lack of clear direction can be frustrating. But the disorientation is also part of the film’s appeal, drawing us deeper into its dark world of intrigue.

The third act takes a surprising turn, shifting from a psychological thriller to a political commentary. It reveals that the eight individuals are not mere captives but trained spies for Kofa, a military organisation on a mission to infiltrate a terrorist group, Tsarkkaken Umma, in the North Eastern region. The twist re-contextualises the earlier events, adding a new dimension to the story and giving the characters' ordeal a sense of purpose.

However, the film’s transition to a political theme is abrupt. Its earlier momentum falters as it struggles to tie together its various plots in the closing act. Though it raises salient questions about the country’s insecurity and the manipulative acts of some government officials, the pseudo-political ending lacks the impact it strives for. It only brushes the surface, leaving much of its political commentary underdeveloped. By introducing a political subplot in the final act, Idada appears to aim for deeper meaning, yet this move softens the film’s original psychological grip and spirited defiance.

Due to the film’s capricious nature, the performances are erratic and unconvincing. Wale's (Daniel Etim Effiong) over-the-top mannerisms and incessant chatter to appear intelligent come across as forced, making his acting uninteresting. Nnenna’s (Ijeoma Grace Agu) quiet demeanour and understated intellect fail to impress. Gina Castel's role as Tosin (a tribute to the late Tosin Bucknor) is noteworthy as the spiritual and surprisingly assertive lead. The remaining ensemble, including Efa Iwara, Kate Henshaw, and Paul Utomi, oscillates between serviceable and forgettable. Their characters lack the profundity and consistency to handle the film’s shifting tones when necessary.

The film’s camerawork effectively captures the claustrophobic setting, using tight shots and low lighting to create an oppressive atmosphere. The use of drones and surveillance footage adds a modern, technological edge to the film, contrasting with the primal fear and confusion of the captives. The editing is brisk, keeping us on edge and maintaining a sense of importance throughout. The film’s score is haunting, using minimalist compositions to underscore the tension and unease. The deliberate use of silence in the dark, dingy room intensifies the characters’ vulnerability and solitude.

Notably, the film’s title, Kofa, a Hausa word for ‘door’, is a clever metaphor about the concept of the human mind as the ‘door’ within one’s body, as hinted in the opening monologue.

In a broader sense, this movie marks a rare foray into psychological thriller territory for Nollywood, a film industry often dominated by melodramas, romantic comedies, and socio-political dramas. Its ambition, though flawed, signals a welcome boldness and genre experimentation in contemporary Nigerian cinema.

Kofa is streaming on Prime Video.